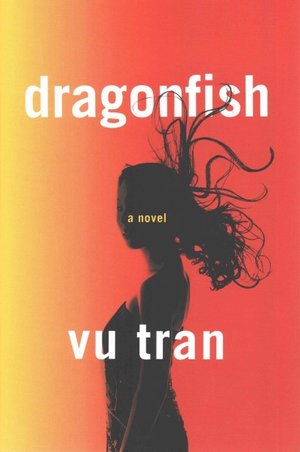

I think that Vu Tran’s impressive debut novel, Dragonfish (2015) is “genre-blending” rather than “genre blurring.” It is a detective story in the noir subgenre of trying to find a troubled, enigmatic woman. I would not label Vietnamese refugee (ca. 1977 by boat) Hong/Suzy (born in 1953) as a “femme fatale,” but Robert, the (white) Oakland policeman (born in 1955, I think) who is the narrator, will never get over his ex-wife, who left him after eight rather manic-depressive years. There is the tortured romance angle (Hong’s second and third marriages). The novel is also a ghost story and alternates between Robert’s trips to Las Vegas to find and/or avenge her, and a long account of a horrific nine-days at sea between Vietnam and Malaysia that Hong wrote for the daughter whom she took with her. (“Refugee narrative” is another of the genres juxtaposed in the book.)

Her first husband, back in Vietnam, had been a captain in the AVN air force, who was shipped north for prolonged “re-education”/torture, and returned after being diagnosed with advanced and terminal cancer. He did not want their daughter to remember him dying and dispatched them on the nearly fatal boat trip, one that was fatal to several other passengers. On the Malaysian island that has been made into a refugee camp, mother and daughter watch a brutal 31-year-old former AVN soldier and his very handsome young (7?) son. (The wife/mother drowned on the boat in which the other four successfully fled.)

In America the father (Son/Sonny Nguyen) and son (Jonathan Nguyen) prosper, though the father is a heavy drinker and high stakes gambler. Jonathan runs some restaurants and tries to minimize damage all around, including to Robert, who learns that Son had thrown Hong down a staircase and decided to go rough him up. By the end of the novel, the reader will believe that Jonathan tried to protect Jonathan.

There are hired , though Son has plenty of muscles in his own bullish body, plus a Vietnamese best friend of Hong’s, “Happy,” who has become a Las Vegas casino dealer… and who also tries to protect Robert. And I have failed to mention that Hong abandoned her daughter, Mai, after a year or so living with her late husband’s uncle (“great uncle” in standard American usage, though Tran has him referred to as “grand uncle”). Mai grew up to be a professional poker player.

I find it hard to believe that she has no memory of her father from her last year in Vietnam (when she was five years old, the same age as the author when he and his mother escaped by boat to Malaysia; his father, who had been a air force captain, had left before he was born) or of the surrogate father and his son (Son and Jonathan), each of whom saved her life while all were in the Malaysian refugee camp. I find it even harder to believe that the terminally traumatized Hong could write so smooth a narrative of her life in Vietnam, Malaysia, and California with the daughter whom she abandoned after all the travail of saving her and getting her to America. (Written to Mai, who has not seen her for two decades, it comes in three installments, including two pages at the onset of the book.)

(2015 photo by Jeffrey Beall from Creative Commons)

Oddly, I find the Saigon-born (ca. 1975) author’s narration by the white cop more credible than that of the Vietnamese refugee. (In a NPR interview he said that “I didn’t have to fight to get that [Hong’s] voice out.”)T his somewhat amuses me given all the huffing and puffing about “appropriation” of “the other,” which is never applied to nonwhite writers writing of/about white characters. Yes, I recognize that though Vietnam-born, Tran is not a woman, either, and I really would not want the long narrative in the broken English of Happy’s dialogue. Moreover, the recollections of Malaysian exile are quite interesting. And the melancholy of Robert’s quixotic Las Vegas crusades and the atmosphere of Las Vegas are very convincingly conveyed by Tran. (BTW, he grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, apart from any Vietnamese American enclave. He teaches creative writing at the University of Chicago.)

©2017, Stephen O. Murray