[Rating:3.5/5]

Pros: suspenseful part

Cons: disingenuousness

In 1977, when distinguished film director Fred Zinnemann (born Jewish in the Hapsburg Empire, educated in Vienna, working in Berlin before Hitler came to power) directed “Julia,” a melodrama celebrating Lillian Hellman carrying money hidden in her hat to Nazi Berlin to her childhood friend and ca. 1934 part of the resistance to Hitler inside Germany. “Julia,” the story was presented (and widely) taken as nonfiction. Hellman’s disingenuous self-glorification (in the 1976 Scoundrel Time) for standing up to the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952 (in a way that Arthur Miller had, but she had not). Her 1973 memoir in which the yarn appeared, Pentimento, had not been publicly challenged.

On a Dick Cavett Show appearance in 1979, Mary McCarthy said of Hellman: “Every word she writes is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the’.” Although obviously hyperbolic, McCarthy and Cavett and the PBS station where the broadcast was recorded were sued for defamation. That Hellman had significantly misrepresented her HUAC appearance and had never even met the model for Julia (Muriel Gardiner) came out, though the case was not dismissed because the judge did not think Hellman was a public figure after decades of public stances, four purported memoirs, and had appeared in a Blackglama fur advertising campaign with the tagline “What becomes a Legend most?” and no (need for) identification of the model (poseur). Considerable doubt was cast on the veracity of Hellman’s account of her relationship with Dashiell Hammett (author of “The Maltese Falcon” and “The Thin Man”), too.

In 1984, Samuel McCracken reported “that the funeral home in London where Hellman said Julia’s body was sent to did not exist, there was no record that Hellman had sailed to England to claim Julia’s body on the ship she said she had made the transatlantic crossing on, and there was no evidence that Julia had lived or died. Furthermore, McCracken found it highly unlikely, as did Gardiner, who had worked with the anti-fascist underground, that so many people would have been used to help Hellman get money to Julia, or that money would be couriered in the way that Hellman said it did.”

Seeing the movie again knowing that insofar as the story has any connection to historical realities, they are purloined from Gardiner (whose memoir had been in the hands of Wolf Schwabacher, who was also Hellman’s lawyer) detracts from being swept up in admiration for the heroism of Julia, and the reflected glory of Lillian’s expedition, but the journey to Nazi Berlin is, with “Day of the Jackal” (1973) and, indeed, “A Man for All Seasons” (1966), an example of Fred Zinnemann’s ability to generate suspense in viewers who know the outcome is. Dick Sargent won an Oscar for best adapted screenplay and Walter Murch was nominated for his editing.

I find the adolescence flashbacks to Lillian’s admiration of Julia harder to swallow than the suspense movie. They are mawkish and also involve inflation, in this instance making Lillian’s bosom best buddy an English aristocrat, though Hellman grew up in America (New Orleans and New York City). To paraphrase McCarthy, there is much false in every aspect of Helmman’s portrait of “Julia.”

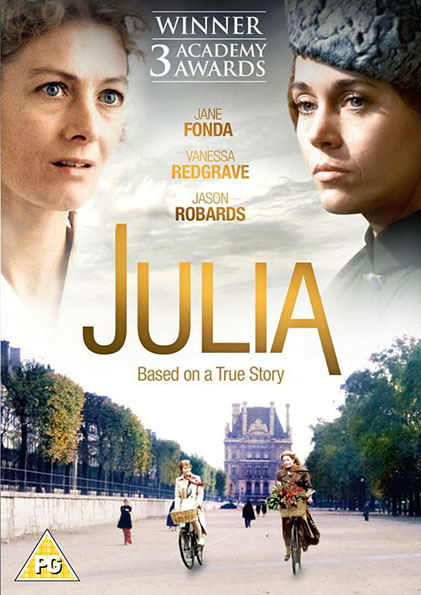

The young Julia and young Lillian were played partly by Vanessa Redgrave and Jane Fonda (respectively), partly by Lisa Pelikan and Susan Jones. Redgrave won her best supporting actress Oscar primarily for the Berlin restaurant scene in which she receives the money and asks Lillian to care for her infant daughter if something happens to Julia. (The daughter, of course, is another Hellman fantasy, along with the death of the Anglophone in Berlin resistance figure.)

There was a campaign against awarding an Oscar to Redgrave because of her support for a Palestinian state. I think that Redgrave should have won an Oscar later for her performance in “Howard’s End,” but question her win for “Julia” for reasons other than her politics. The competition, however, was not intense; Jason Robards’ Dashiell Hammett won in a stronger field (including Maximilian Schell in “Julia”) for best supporting actor. (Sargent also had weak competition.)

The 40-year-old Fonda and Redgrave (both were born in 1937) playing scenes as a youth in their early 20s requires willful suspension of disbelief. But I also find Fonda as a frustrated writer difficult to believe (though throwing her typewriter out the window is something I remembered form seeing the movie on its original release). Moreover, Fonda was far too beautiful to be credible as Hellman of any age. (As Annie Hall, Diane Keaton won the best actress Oscar for which Fonda was nominated.)

I think that “Julia” was/is overrated, though Zinnemann’s mastery is underrated. (He only made one more film after “Julia,” “Five Days One Summer” (1982), which I have not seen.) BTW, it was a question about overrated writers that stimulated Mary McCarthy’s slam of Hellman. IMHO, the problems with “Julia” are in the source material, which was not known in 1977 and might not have been known late had Hellmann not sued.

Zinnemann’s previous movie, “Day of the Jackal” was based on a novel based on a real assassination plot and is great fun.

©2018, Stephen O. Murray