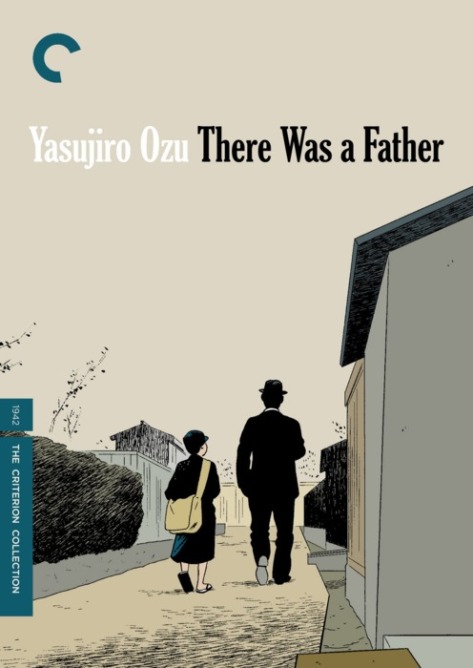

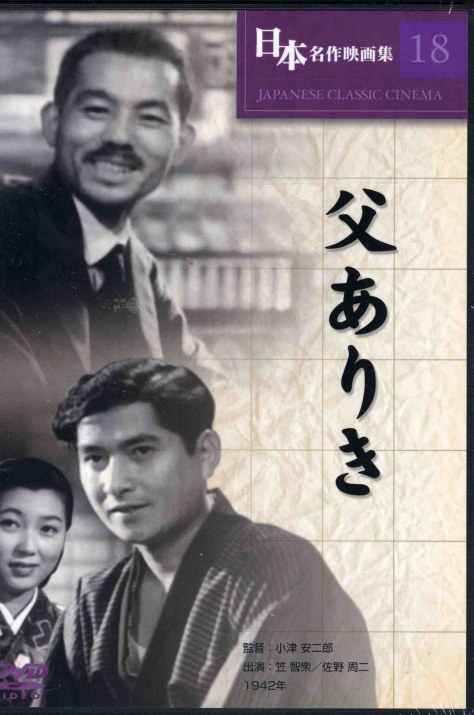

Between 1938 and 1946 Ozu Yasuojirô (1903-63) made only two movies. (An army reservist he was called up twice and was away from Shochiku Studio for three of these years). The second of them “Chichi Ariki” (“father from Ariki, which is where the son goes to teach chemistry; titled in English “There Was a Father”, 1942) does not mention any of Japan’s wartime enemies, and barely touches directly on military matters—the now 25-year-old son passes his draft physical, which is not surprise in that for a Japanese, he is a hulk. At the end, rather than going off for military service, he is returning, with his new wife (Fumiko [Mitsuko Mito], the daughter of his father’s friend and go opponent) to Ariki, carrying his just-deceased father’s ashes in the luggage rack above his seat in the train.

The widower father, Horikawa Shuhei (Ozu regular pater familis Ryû Chishû) moved to Tokyo midway through the film, but dies of a heart attack, rather than from American bombs — which were not yet blanketing Tokyo when the movie was shot. When the present-day of the movie is remains opaque. It is thirteen years after Horikawa resigned from being a middle-school math teacher after a boy in his charge — defying explicit orders not to go out in boats on the lake the school group was visiting — drowned.

No one but Horikawa blamed him from the accident. His colleague Hirata (Sakamoto Takeshi) in particular urges him to stay, but Horikawa retreats to his native town of Ueda, staying with an old friend who is a priest. Horikawa realizes he needs to make more money than he can in Ueda in order to send his son to (middle) school and moves to Tokyo, where he works as a low-level manager in a textile factory.

The son, Ryohei (played by Tsuda Hahuhiko as a child by the hunky Sano Shûji as an adult) being inculcated in Duty, Duty, Duty, has to live in boarding school, longing for occasional time with his father. They spend their time together fly-fishing in a rocky stream (in which as far as I can tell, they never catch a single fish) and deferring to each other about who will bathe first.

Ryohei continues to long to live with his father, but when he proposes coming to Tokyo and finding a job, his father erupts with a lecture about his duty to stay where he is and teach those who are the future of the Empire. Teaching is vital work, never mind that Shuhei himself abandoned it in guilt (or shame?) after the boy’s drowning and, in effect, has punished his son for his own sin of omission (at least a failure of watchfulness over his charges). Sacrifice is not only necessary, but good (a message the brunt of which is borne by daughters in later Ozu movies).

Though there is no propaganda for Japanese militarism in this — let me stress 1942 — movie, its inflexible call to duty in general, and keeping one’s place in the society, submitting to paternal authority, pleased the government authorities in charge of the Japanese movie industry (after 1939). The movie was a critical and commercial hit, even without any battle scenes and without any of the women sacrificing themselves to their vision of what the family needed, as was common in Ozu’s more famous postwar movies.

Ryû was good and at least in the first half played his own age. Both Ryoheis were also good, swallowing their hurt (and tears). The Ozu camera was already fixed at the height of one meter, but the intercutting kept it from seeming visually static. And there were some outdoors scenes: not only trains, which recur in Ozu movies, but the trout stream.

I’ve already noted that in commanding his son to stay at his teaching post, Horikawa Shuhei is effectively saying “Do as I say, not as I did.” As with later fathers Ryû played in Ozu films, Horikawa Shuhei downs a lot of sake.

©2017, Stephen O. Murray

The other movie Ozu made during the war, which has the more typical female self-sacrifice, was Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family (1941). For my other reviews and ratings of other parts of Ozu’s oeuvre see here.