Virginia Woolf’s first great novel Mrs. Dalloway (1925) with its multiple streams of consciousness would seem a canonical modernist work ill-suited for adaptation to the screen. However, the highly disjunctive text proceeds in ways very similar to the montage of jump-cuts championed by Soviet film directors. (I have no idea what, if any cinema Woolf was familiar with.

)

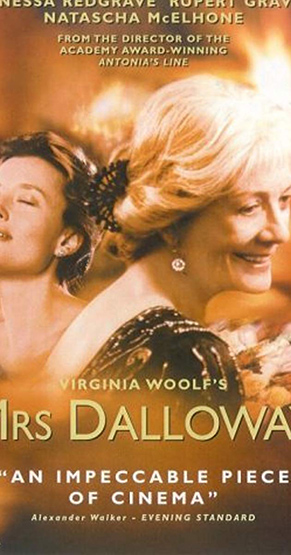

Although the novel has very little plot, the cinematic jump-cuts of the text work even better on screen than on the page. Credit for this can be shared between the 1997 film’s editor Michiel Reichwein, director Marleen Gorris (Antonia’s Line, The Luzhin Defence) and award-winning actress and co-creator of “Upstairs/Downstairs” (Dame) Eileen Atkins. The director, scenarist, and star (Vanessa Redgrave in the title role) also manage to transport from page to screen the interior monologue of Clarissa Dalloway. Those three and two companions of Clarissa’s youth who unexpectedly turn up the day of the party she is showing, Peter Walsh who never got over having his heart broken by Clarissa’s choosing the safety of marriage to Richard Dalloway, and Lady Rosseter, with whom (as Sally Selton) the young Clarissa was more in love than she was with her intimate friend Peter or the man whom she would marry. The actors portraying the worn-down, older Peter (Michael Kitchen, Doyle of “Doyle’s War” and the king of “To Play the King”) and even more transformed former Sally Selton (Sarah Badel) and still-vague older Clarissa (Redgrave) make the transformations from their golden (OK, verdant) last summer of youth very, very visible. Sally, transformed into Lady Rosseter and the mother of five strapping sons, is the only one who seems content with the changes from the yearning, hoping youths to the elderly observers of life.

The more passionate young incarnations (Natascha McElhone as Clarissa, Lena Headey as Sally, Alan Cox as Peter) are different characters as the camera shows them maneuvering—and being outmaneuvered by the already stolid Richard Dalloway (the young one played by Robert Portal, the long-married Member of Parliament who is never going to make it into the Cabinet, by John Standing). There are continuities of temperament from the young to the old incarnations, but the physical differences are more striking on the screen than on the page.

What is lost in adapting the novel for the screen is the subjectivity (streams of consciousness) of the characters other than Mrs. Dalloway. Peter and Lady Rossiter, Peter and Clarissa, Clarissa by herself, and even Richard Dalloway recollect the summer that ended with Clarissa’s accepting Richard’s marriage proposal, but with screen flashbacks (and the objectivity of the camera), they all seem to be remembering everything as it was, not selectively and subjectively distorted as the book’s character’s memories (flashbacks). That is, they all seem to have direct access to unmediated, uninterpreted events of that summer. The reader of the book knows which character is recalling what. The viewer of the movie cannot easily guess whose memory is being displayed on screen.

The exception, the most searing flashbacks and hallucinations of events being repeated, is a character whom first Mrs. Dalloway and then Peter glimpse on the day of her party, but do not know (though the party will be marred for Mrs. Dalloway by hearing about), Septimus Warren Smith (played by Rupert Graves, who has frequently appeared in films of that era, including “Maurice,” “A Room with a View,” and “A Handful of Dust”). Septimus is haunted by memories of a friend being blown up during the last days of the First World War (five years before the narrative’s present day). That scene is the very first one in the movie. Septimus is suffering what was then called “delayed shellshock” and now would be labeled acute “post-traumatic stress” mixed with acute survivor’s guilt. His subjectivity is not conveyed by voice-overs as Mrs. Dalloway’s is, but the viewer sees the hallucinations he does, and his thoughts about not being able to feel are expressed aloud in the movie.

I think that the book is less about the title character than about surviving (Mrs. Dalloway) and not surviving (Septimus) guilt about the past and the depressive lows of manic-depressive mental illness. By starting with the most traumatic of Septimus’s war-time experiences, the movie seems to be headed for making Septimus as central as Clarissa, but I’d say that the movie is more about regret. (Peter’s, Clarissa’s, Septimus’s, and to some extent Septimus’s Italian wife, milliner Rezia (played with foreboding and helplessness by Amelia Bullmore).

Vanessa Redgrave’s Mrs. Dalloway starts out positively giddy. I thought the title character of the book was fighting off an undertow of depression not unlike her creator. The movie introduces a manic phase, too, with the euphoria about the beautiful day as Mrs. Dalloway strides out to buy flowers. She is not manic during the party, though what she is feeling is quite different from what she is saying as an attentive hostess. After she hears about the shellshocked soldier, she sinks into a depression, but, unlike Septimus, survives it. During the day before the part, Septimus has both manic and depressive episodes (that is, very rapid oscillation).

Many screen adaptations of canonized novels illustrate them prettily. The adaptation of Mrs. Dalloway transports everything of importance about the characters, the events and memories of the day of the Dalloway part, and the party itself to the screen. To an unusual extent (contrast the mess of the screen transfer of another novel with multiple streams of consciousness, The Sound and Fury to the screen), the spirit of the book made it across the change in medium. For all the excellent acting, costume and set decoration, photography (Sue Gibson), etc., “Mrs. Dalloway” is more a worthy movie than great cinema. But because it is a very cinematic adaptation that I can find no fault with, I give it a five-star rating. I do not think it is a great movie, but it is a superlative recreation of a great novel, that in some ways improves on the novel (by making the changes in the late-middle-age characters from their youthful avatars painfully palpable). It also does not contain any extraneous material, which I would not (in fact did not) say about the novel.

I still have to pronounce the book better, because the book has multiple subjectivities, and, because Vanessa Redgrave is so incandescent (even without monopolizing the interior monologues) that it is difficult for others to register with viewers (in the film’s present day; Natascha McElhone’s junior Clarissa stands out, too, but the other youth have a better chance to register on the viewer, since all are being shown and the viewer is not privy to what they are thinking beyond reading their looks). The star throwing the balance of an adapted off kilter is common. Redgrave does it without monopolizing screen time or upstaging anyone.

©2018, Stephen O. Murray