Although Joan Crawford made many movies that have not seen, it seems that most cast her as a determined-to-rise and quick-study woman from the wrong side of the tracks. Her characters have to overcome considerable disdain from those born to the upper class and flashes of self-doubt. Although she often seems to be using men whose status is higher than their IQs or will, generally the screenplays try to make the audience believe that she really loves the men and give her chances to prove devotion beyond her interest in securing and maintaining a status in the elite of whatever locality she is operating in.

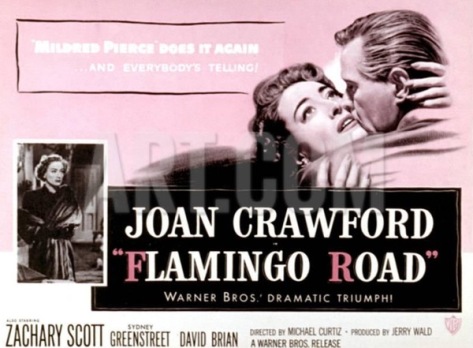

The 1949 “Flamingo Road,” based on a long-forgotten best-selling novel, sticks to the formula; indeed it reunites director (Michael Curtiz), male and female leads (Zachary Scott and Crawford), and, unfortunately, supplier of frenzied overkill music (Max Steiner) from “Mildred Pierce,” the overwrought melodrama that revived Crawford’s career after she was dumped by MGM and won her an Oscar.

I have been watching a number of late-1940s movies in which the leads were far too old for their parts (Greer Garson in “Valley of Decision”, Barbara Stanwyck and Van Heflin in “B. F.’s Daughter”), but at least those other movies covered long spans. Even with repeated reference to being tired of knocking around, Crawford was fifteen years too old for the part of the traveling-carnival exotic dancer who does not flee with the carnival. She was also ten years older than Zachary Scott, who was also 5-10 years too old for the part of Fielding Carlisle, the son of the deceased, highly respected Judge Carlisle and protégé of the local boss eager to use that family name.

The boss, Sheriff Titus Semple (played with cold, calm menace by Sidney Greenstreet), has made Field a deputy sheriff with few responsibilities, but sends him to serve papers attaching the carnival for nonpayment of debts. The only remnant of the carnival is a tent in which Lane Bellamy (Crawford) is listening to the radio. Field takes her to a diner and gets her a job waitressing there. Such a romance does not fit with Titus’s plans. He more or less orders Field to marry a member of the local elite (those who live on Flamingo Road) Annabelle Weldon (Virginia Huston).

Titus also makes Lane disappear, having her picked up and thrown in jail for 30 days for soliciting prostitution. Lane is not so easily driven off. She makes some interesting alliances with a man and a woman of some independence from Titus. Much of the fun of the movie is watching Crawford and Greenstreet glower at each other while making polite talk in front of others., Eventually, they have it out alone in private.

In that Crawford really did rise from the wrong side of town through dancing and marrying up (ultimately to the president of Pepsi Cola), as well as making a career out of playing upwardly mobile women, her clawing her way up the social (/economic) ladder is believable. The problem is that her character could not possibly have kicked around as a second-string feature in a third-run carnival so long before starting her ascent. The incongruity of the 45-year-old in the part of Lane is only made more glaring by the repeated references to her as a “girl.”

What redeems the movie is the relentlessness of the story and of the antagonists. In the immense Sidney Greenstreet, Crawford had a rare male worthy opponent. (The only time I can think of that Crawford was overmatched was by Bette Davis in “Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?”, though Mercedes McCambridge in “Johnny Guitar” and Ann Blyth in “Mildred Pierce” were formidable in their hatreds of her.) In earlier roles (Maltese Falcon, Casablanca) Greenstreet played grasping, amoral characters with a certain amount of sardonic charm. Titus is content for people to maintain their stereotypes of joviality being a concomitant of fat, but is a completely cold-blooded grafter. His smiles are mostly grim. If he has any emotions, they are so well padded that they do not emerge. As Crawford goes from being potential trouble for his plans to being a clear-and-present lethal danger, he never shows anger. He drinks pitchers of milk, rocks on the porch of the Palmer House Hotel, collects his graft in cash, minimizes movements, and pulls strings to bring down anyone who gets in his way.

Zachary Scott was good at being pushed around (as in “Mildred Pierce”). Gladys George played savvy survivors in many movies and provides a leavening of wit to the fast-rising melodrama. Fred Clark plays against type, an idealist newspaperman who dares to criticize the corrupt state and local government (which state is not specified; from the title, one might think Florida, a state that democracy still has not reached; but the milieu seems as western as southern). David Brian plays a peculiarly written role of a builder who became a political boss because contracting in the state was so corrupt that he could not be an honest builder. He falls fast and hard for Crawford, which ensures that Greenstreet will arrange legal troubles for him.

If one can accept Joan Crawford starting her move upward looking obviously more than 40, and enjoys watching evenly matched characters battling to the death like a mongoose (Crawford) and a cobra (Greenstreet), “Flamingo Road” is a lot of fun. It certainly has a consciousness of class that is missing in third millennium American movies (to take an instance with another machine-picked politician named Fielding, “Waking the Dead”). For all its cynicism about electoral democracy, like so many late-40s Hollywood movies, “Flamingo Road” affirms the American dream of rising in the social and economic hierarchy through individual effort, making it is an interesting document of postwar American ideology. It also shows that 1949’s Oscared “best picture,” “All the King’s Men,” was not unique in portraying graft-ridden government and political bosses (which Preston Sturges had already done in “The Great McInty,” anyway.) A bonus is the nourish look provided by cinematographer Ted D. McCord (Treasure of the Sierra Madre, East of Eden).

©2002, Stephen O. Murray