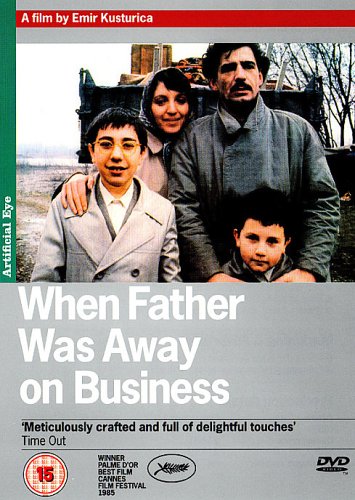

“Otac na sluzbenom putu” (When Father Was Away on Business, 1985, directed by Emir Kusturica) is the most-honored film to come out of Yugoslavia (“WR: Mysteries of the Orgasm” is the most notorious). “Otac” won the Palme d’Or, the top prize at Cannes unanimously, and was nominated for an Oscar and a Golden Globe as best foreign-language film (losing to “The Official Story” from Argentina in both cases).

“Otac na sluzbenom putu” is a quite (excessively!) long — 136-minute — story of a family having marital and political troubles when Malik Zolj (Moreno De Bartolli) was a six-year-old, living in Sarajevo (, Bosnia). Although the film is primarily told from the viewpoint of Malik, it opens with his father, Mesha Zolj (Miki Manojlovic), and his mistress, Ankica (Mira Furlan), on a train headed back to Sarajevo. She is impatient for him to divorce his wife, Senija (Mirjana Karanovich), and marry her. It is soon obvious to the viewer that he has no intention of leaving his two sons.

On the train he derides a cartoon of Karl Marx writing at a desk with a picture of Josef Stalin on the wall. The time is 1950, two years after Josip Tito had broken from the Soviet Empire (though certainly not from Stalinist organization of the economy and surveillance of citizens and Yugoslavia had been expelled from the Communist Information Bureau (Cominform). Those who had embraced Soviet leadership and failed to turn on the dime to deriding Comrade Stalin were labeled “Cominformists” and were rooted out.

The father of Malik’s best friend, “Fatso,” has been disappeared. Malik’s mother’s brother, Zijo (Mustafa Nadarevic), is the local head of the State Security apparatus… and has taken up Ankica, who has told him of some of Mesha’s comments about the ridiculousness of the sudden shift form deification to demonization of Comrade Stalin. Zijo allows Mesha to attend the party for his son’s genital mutilation (AKA circumcision—this is the first, and pretty much only, indication that the family is of Muslim background, though Mesha is a long-term communist and atheist).

Rather than just disappearing in the night, Mesha is allowed to give the appearance of leaving on a business trip — hence the title. In fact, he is consigned to mines and later to a “resocialization” position building a hydroelectric plant on the Drina River.

In one of the more dramatic scenes of the film, Senija goes to her brother seeking information about what has happened to Mesha. He advises her to mind her own business — as if the extended absence of her children’s father is not her business. She wants to send a package of warm clothes to Mesha. After Zijo says that this is not possible, she snaps at him that it was possible when Mesha was imprisoned during the war by the Utashe (the Croatian fascists allied with Hitler who rules Bosnia as part of “the Independent State of Croatia”). That Zijo had been a fascist police official before becoming an upholder of communist/Titoist orthodoxy is a point likely to be missed by those not familiar with Balkan peninsula history (or not paying close attention).

Senija and Mesha are understandably bitter at the failure of Zijo to protect his brother-in-law, and, indeed, for reporting forbidden attitudes. Senija is also understandably angry that it was while philandering with another woman that Mesha was politically indiscreet.

Malik understands little of this, though he cannot fail to notice that his maternal uncle stops coming around at the same time his father has gone away. The family is reunited at what is dubbed “Wetland,” where Mesha is some kind of supervisor on the hydroelectric project. Malik falls in love with Mesha’s Russian physician friend’s sickly daughter.

The young actor is not replaced, so that it seems the whole trajectory of the exile and rehabilitation of his father occurs in a matter of months, when surely it took years. Moreno De Bartolli is good, but isn’t so good that the part of Malik could not have been split with an older boy (IMO). He is not, for instance, as compelling as Dimitrie Vojnov in the more satiric Yugoslavian film about the Tito cult and one family (and another plump child) in “Tito i ja” (Tito and Me, 1982, directed by Goran Markovich) set in 1954 Belgrade.

The film is not without humor, which includes aspects of Malik’s romance, his sleepwalking (which I don’t find convincing), and his sabotages of his father’s sex life (marital as well as extramarital) and Malik’s paternal grandfather who lives with them.

I don’t think the film needed to exceed two hours in length. The easiest cut to make would be the opening song. Not that I dislike the song (in Spanish), but the character who is introduced has not part in what follows. Many other scenes unfold at a pace that may have seemed leisurely in 1985 but that seem dragged-out in 2007.

The film has special interest to me for its portrayal of politics and its portrayal of interethnic comity in Sarajevo (Fatso’s family is Serbian, but this can only be inferred from a funeral for Fatso’s father). The child perplexed by what is upsetting the adults is, I think, easily grasped by anyone, even someone completely ignorant of the political dynamics of Bosnia in the 1940s and 50s.

The video transferred looks very 1970s. Definitely, it was not remastered. The DVD includes a dozen trailers for other Koch-Lorber releases, and an eighteen-minute and IMO not very informative or lively interview with director Emir Kusturica.

BTW, Kusturica was born in 1954 in Sarajevo to a Moslem Bosnian family, but his father disavowed religion to become a Yugoslavian Communist. And “Otac na sluzbenom putu” is very much a Yugoslavian film rather than a Bosnian one (in the same way that the Nobel Prize-winning The Bridge on the River Drina is Yugoslavian.

©2007, 2017, Stephen O. Murray