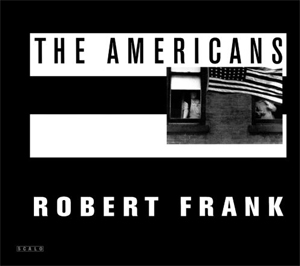

To make “An American Journey: In Robert Frank’s Footsteps” (2009), a half century after Swiss-German-Jewish immigrant photographer Robert Frank (born in Zurich in 1924) took to the road for two years on a Guggenheim fellowship, Philippe Seclier set out to follow Frank’s itinerary and try to find people and places that had made it into Frank’s (1958 in French, 1959 in English) book The Americans. Frank took 28,000 photographs, of which the book reproduced only 83.

In the documentary some people page through the book, but Seclier only shows trying to find the subjects of a handful of the photos. He finds New Orleans trolleys the window in Butte, Montana from which Frank shot the streets and rooftops of a more prosperous mining town), and the location of a shot on Belle Island in the Detroit River without the black and white people who were the point of Frank’s shot. He also finds a black Alabama woman whom Frank shot on the back of a motorcycle and a boy who was in the foreground of a 4th of July celebration in upstate New York (with a very large flag taking up most of the visual field). Both identify themselves in the photos, but neither remembers the photographer or being photographed.

Somewhat more interesting than the failures to connect with the objects of the 1950s photos are some reminiscences of the French and the American publishers (Barney Rossiter of the Evergreen Review and Grove Press was the American one, Robert Delpire the French one), Frank’s New York printer, and a friend in whose darkroom in Orinda (a suburb of San Francisco just east of the coastal mountains) Frank made the first prints of the film he had shot crossing the country. These interview segments are OK. More interesting it the tale of Frank’s youth in Switzerland surrounded by the Third Reich and coming to the US in 1947, where he worked for Harper’s Bazaar as a fashion photographer for a time. After some time in Paris, he returned and did freelance photography published in glossy magazines of the early 1950s.

Edward Streichen and Walker Evans supported his Guggenheim application. The latter wrote a preface for the first (French) edition. The newly famous Jack Kerouac wrote one for the Grove Press American edition. Allen Ginsberg had also befriended Frank, and Frank was best known to me for filming the Beat writers in “Pull My Daisy” and the Rolling Stones in “Cocksucker Blues.” (Frank’s film-making career, and indeed anything beyond the publication of The Americans is unmentioned in the documentary and there is no mention of any attempt to hear from Frank himself.

I know that some criticized blurriness in some of the images in the book, so am somewhat hesitant to criticize the blurriness of many “on the road” shots in the movie. I imagine that Seclier, who credits himself with photographing and driving, had some arty intent, though the blurriness may derive from filming and driving at the same time.

I am not convinced that the book is as important or as seminal as Seclier believes. For the seminal, remember that Frank was supported by Walker Evans, whose photographs in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men documented poverty and racism in the American South. Also dating back to the 1930s, were the powerful images shot by Dorothea Lange (and even Ansel Adams’s documentary photographs of the Manzanar concentration camp for West Coast Japanese Americans during World War II). And Frank’s photographs are not as well known as those of Diane Arbus (with Frank and Saul Leiter, Frank is sometimes identified as a photographic “New York School” paralleling the “New York School” of poets—with whom Frank was not associated).

Mention is made at the attacks on the book for the definite article (the) in the title, a claim for universality or representativeness that was not made in the first two publications of Frank’s photos from on the road.

For the half-century anniversary of the publication of the book, an exhibition was mounted by the National Gallery in DC, and traveled here (the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) and onto China. The documentary ends with a woman walking through the exhibit in Northern China (with a glimpse at the map indicating places where photos in the show and book were shot). She does not say anything about her impressions of the photos.

The documentary might stimulate some viewers (even those who shut off the DVD long before its end, though that is never more than an hour away) to look at Frank’s book, but it is a remarkably dull movie. Painter Ed Ruscha makes some apposite remarks, but Seclier’s meditations are exceptionally banal. For sue, Seclier is not a new Tocqueville!

©2013, 2017, Stephen O. Murray