I have seen most but not all the films that have won top honors at the Cannes Film Festival (the golden palm). I am dubious about some that I have seen (e.g., Barton Fink, Wild at Heart) and actively disliked “Tree of the Wooden Clogs” and “The White Ribbon,” but of the 54 I have seen, the most boring, most inept, and worst is the 2010 winner, “Lung Bunmi Raluek Chat” (Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives), a Thai movie directed by Apichatpong “Joe”* Weerasethakul. The no-budget first Weerasethakul feature, “Mysterious Object at Noon” (Dokfa nai meuman, 2000) tried my patience and the camera bouncing along in a van nearly made me nauseous, but some of the Thai people interviewed had interesting things to say.

The 2002 “Blissfully yours” (Sud sanaeha) seemed enervated and also made me queasy with seemingly endless shots of a rash on the back of a Burmese regufee/immigrant in Thailand. The movie won the Un Certain Regard prize at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival.

“Tropical Malady” (Sud pralad, 2004) consisted of two stories, though both are so opaquely presented “story” might not be an appropriate descriptor. I liked the first one with a homosexual encounter in the forest, and there were some arresting shots in the second one in which a soldier meets a tiger (shaman) in the forest. (Both involve the same two actors.) Though many in the Cannes audience walked out and others booed it, “Tropical Malady” won the Jury Prize at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival.

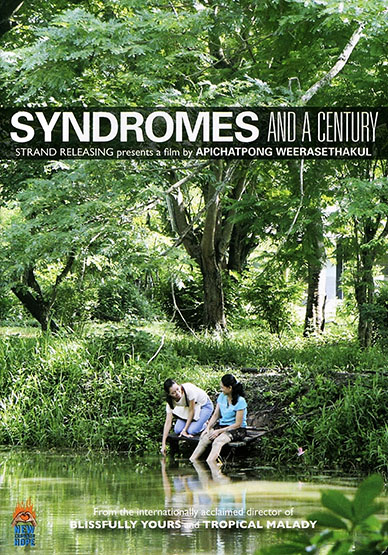

Though also including some seemingly pointless and lengthy forest scenes, “Syndromes and a Century” (Sang sattawat, 2006) seemed to me to show significant development in the film-maker. It was also split into two stories, this time both involving the same pair (this time male and female) in Thai rural hospitals 40 years apart. It did not play Cannes. It was in competition at the Venice Film Festival, but Venice jurors apparently do not share the euphoric enthusiasm for Weerasethakul movies that Cannes ones do. Weerasethakul refused to make the cuts demanded by Thai censors, and the ban in Thailand became a major brouhaha there.

Which brings us up to “Uncle Boonmee: Who Can Recall His Past Lives.” The movie that I find not languid but numbing was greeted with critical praise in America as well as the Cannes top prize. I have no explanation for this. The movie does not provide the sort of puzzle that “Last Year at Marienbad” or “Blow-Up” did. There are a series of long and static shots (plus one handheld camera going into a dark cave that is jumpy in the “Mysterious Object at Noon” tradition) in which the dead come back to chat with Boonmee, whose kidneys are failing. (He is cared for by a Laotian who has crossed the Mekong illegally, should anyone be interested.)

Since one of these is his wife, the woman I first took to be his wife must be a sister or sister-in-law (she is counting the take after the funeral in the last part in a hotel room with her daughter and a stray Buddhist monk who wants to shower, but whose room does not have warm water…). The most ludicrous is a son in dime-story Wolfman suit with red lights for eyes. There is also a never seen water sprite who talks to the woman (at great length from a pool in which she gradually enters and floats).

I have read reviewers who claim the movie illuminates Thai(/Buddhist) belief in reincarnation, but I did not register any reincarnations. There are ghosts, one of whom says that ghosts attach to a person rather than a place. Boonmee feels guilty about all the communists he killed earlier in his life. Boonmee goes into the forest just before dying, but I think he will turn into a ghost, not immediately be reincarnated there or anywhere else. In addition to the ghosts and Ed Wood-level special effects, the movie also includes intimations of sex with a catfish, a princess in quest for eternal youth, a long look in the near dark at a water buffalo in a forest stream, characters splitting in half (so they can continue to watch tv and go out to eat), and the monk’s undressing, showering, and dressing (discreetly filmed above the waist, btw). If I have made the movie sound interesting, please believe me that I found it tedious and amateurish (“Ed Wood-level special effects” is not a compliment!)

I also fail to see a “meditation on the afterlife” (my local newspaper critic claimed the movie was that), though there is a discussion with one of the ghosts (in which she says heaven is very boring as well as the ghosts haunting individuals not being attached to a place). I am interested in Thai culture and have traveled through much of the country (as well as being a veteran of slow and opaque scenes in Weerasethakul movies!).

* Weerasethakul studied (Andy Warhol’s “Sleep” perhaps) at the Chicago Art Institute, hence the “Joe.” The DVD has many bonus features including his talking about the movie. I doubt that this would convince me that “Uncle Boonmee” is great and profound, though bonus features often increase my appreciation and valuation of movies.

©2011, Stephen O. Murray