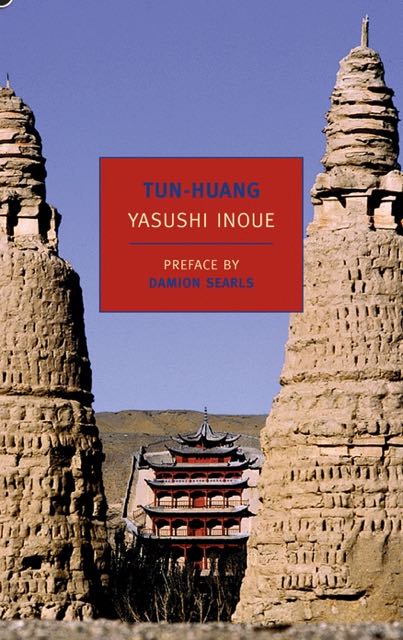

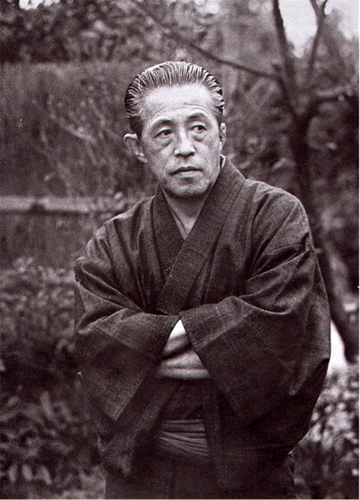

Inoue Yasushi won all the major Japanese literary awards during his lifetime (1907-91), but it was the New York Review Books reprinting of Tun Huang (winner of the 1959 Mainichi Press Prize) that brought him to my attention.

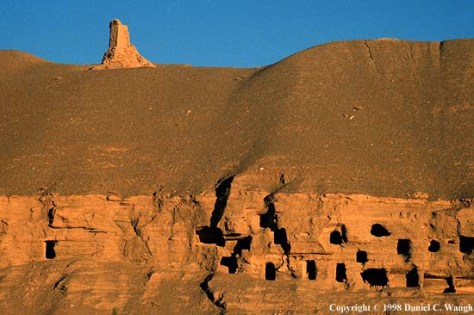

I went back to his earlier novellas set in (then-)contemporary Japan, including ‘The Hunting Gun’, for which Inoue won Akutagawa Prize, then undertook reading ‘Fūtō´ (which won the 1963 Yomiuri Prize, but was not translated into English until 1989, as Wind and Wave’s ). This novel does not fill in a gap in the historical record (as Tun-Huang did, providing an account of how a trove of Buddhist scrolls came to be sealed into a cave) with imaginary characters

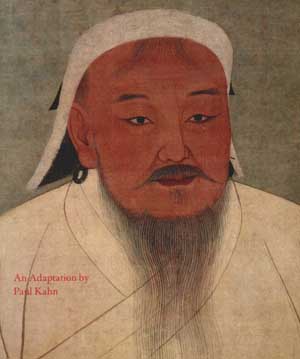

The 200-page book begins with a dramatic personae running four and a half page. The only familiar name was Kubilai Khan (the Mongol Great Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, founder of the Y¼an Dynasty, whose name is usually rendered without the middle syllable in English, as Kublai; the current (pinyin) romanization is “Hūbìliè”). I knew that Kubilai twice sent large fleets to conquer Japan and that most of the soldiers drowned en route.

Surprisingly, especially in a book by a Japanese author (and one who wrote several books set in interior Asia, including Blue Wolf , about the early life of Genghis Khan), the focus of Wind and Waves is entirely on Goryeo (Korea), as its kings and their ministers attempt to preserve some autonomy and to reduce Kubilai’s demands for soldiers, sailors, and ship-building (stripping the forests of the south of the peninsula).Both kings journey to Kubilai’s court multiple times and feel some kindness from the Great Khan, though his sympathy waxes and wanes and keeps not only the kings, but various Koreans directly serving the Mongols guessing. (There are multiple plots to overthrown the Goryeo kings, vassals of the Great Khan).

Most of the book is preparations for the huge and disastrous attempted invasions of 1274 and 1281. There is very little about what happened to the armies or to the various delegations of Mongols the Koreans were forced to take and accompany to Japan (where most were not allowed onto Honshu, where the capital was). The Korean ships made it to the southernmost of the large islands of the Japanese archipelago, Tsushima and Ikiand, and unloaded 40,000 troops. The large Chinese fleet, transporting 100,000 troops was supposed to rendezvous there with them, but was delayed by storms.

With a tsunami of unfamiliar names, many official letters, and no sex, the book seems very much like a thirteenth-century chronicle, though to some degree getting inside the Korean kings, imagining what they and their chief ministers thought about their very difficult position-between the treacherous seas and demands from an overlord completely unfamiliar with seaworthy vessels and as unable to imagine resistance to what he was certain was a clear “mandate from heaven” or to conceive that the Japanese considered their emperor directly descended from the sun and Japan as impregnable. The Japanese writer ever explicitly makes no Japanese perspective in the book, and apparently the novel met with approval by Korean scholars (despite the considerable anti-Japanese animus in Korea).

Though the book is tough going, I doubt I would otherwise ever have considered what it was like to be vassals of Kubilai Khan ordered to outfit and partially man an invasion the Koreans dreaded, (The English title comes from the Great Khan’s demands that his emissaries to Japan be carried there without high winds and waves being an acceptable excuse for failure.).

©2016, Stephen O. Murray