Inagaki Hiroshi (1905-1980) was a master of samurai films shot in color, best known for the Samurai Trilogy (1954-56) with Mifune Toshirô playing the legendary swordsman Musashi Miyamoto, and a 1962 adaptation of Chuchingura (47 Ronin). His very last movie, “Machibuse” (“Incident at Blood Pass,” 1970) is the only one of his that I know of that fits within the late-1960s “ronin rebel” subgenre. Mifune starred in and produced it.

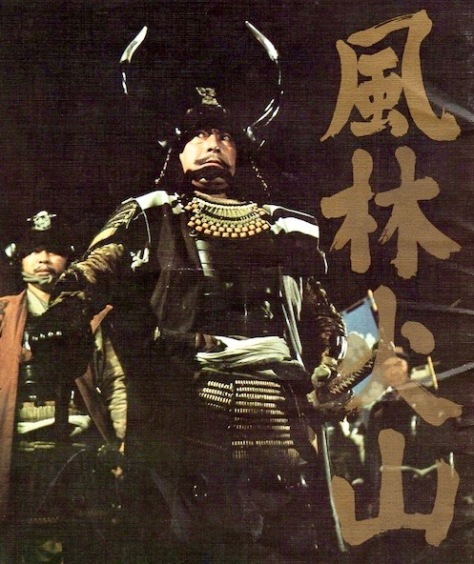

The year before he produced and starred in what was at the time the most expensive Japanese movie ever shot, “Furin kazan” (Samurai Banners),* an epic about a ruthless strategist, Yamamoto Kansuke (Mifune) bent on unifying the country (by guile and by force, preferring the former). The warring feudal principalities of the sixteenth century were the time of the greatest prestige of the samurai. Yamamoto seems little concerned with the samurai code (bushido—the way of the sword). His interest is in strategy.

He wants to subdue all the neighboring feudal principalities for a child he could be said to have engineered, a son produced by the feisty, independent-spirited daughter and her father’s murderer, Yamamoto’s lord, Takeda (Nakamura Kinnosuke). It is for this boy (the lord’s fourth son) that Yamamoto seeks to conquer the island (Honshu).

The relationship between Yamamoto and Princess Yu (Sakuma Yoshiko) is complex. His devotion is somewhat puzzling to me. Her ambivalence for him is easier to understand, as is her ambivalence to Takeda.

Two-thirds of the way through the movie, Yamamoto tells Takeda that he must become a Buddhist monk (renouncing sex and shaving his head). This has not the slightest effect of cooling Yamamoto’s bloodletting. Takeda wearies of being a puppet and of Yamamoto’s high-vaulting ambition for the Takeda clan.

Takeda at times wants to rest on his laurels and enjoy his conquests, but when persuaded to move his army (frequently!) by Yamamoto, he is very eager to attack. Yamamoto generally checks these impulses of his sovereign.

Indeed, there is not a battle until after intermission (about an hour and a half in). There is scheming, and murder, and Yamamoto taking over planning the future of Princess Yu and the son she bears as well as the grand Takeda strategy. The movie covers nearly twenty years (1543-1562) roughly half a century before the Tokugawa triumph and unified rule (Kurosawa’s masterpiece “Kagemusha” shows Nakadai Tatsuya playing Takeda and a double who impersonates Takeda after he is killed in a later battle.)

The movie has a propulsive musical score by Satô Masaru, magnificent color cinematography by Inagaki’s recurrent cameraman Yamada Kazuo. There are gorgeous panoramic vistas and eye-popping costumes (outlandish helmet, very photogenic armor and kimonos). The movie is a lavish production in which the main characters are not lost.

Indeed, though Yamamoto’s psychology is fairly opaque to me, what he is doing is very clear. Nakamura and Sakuma hold their own with Mifune at his fiercest and most passionate.

The movie runs 166 minutes (epic in length, too!). Despite periodic maps and explanatory titles, the military campaigns and battle scenes are somewhat confusing. And there is a crucial development near the end that I think was missing (rather than that I missed it) in a long-building climax (during the climactic battle at Kawanakajima).

When Kurosawa got funding to make his historical epics (or anti-epics) in color during the 1980s—“Kagemusha” and “Ran“— “Furin kazan” was eclipsed. I also find it less satisfying than Inagaki’s Samurai Trilogy—and prefer the quirkier rebel ronin movies of the 1960s (and Kurosawa’s take on Macbeth with Mifune, from the 1950s, “Throne of Blood”). Still, I think that “Furin kazan” should appeal to those who enjoy epic war movies with unusual love stories mixed into the bloody brew.

The DVD transfers are pretty good. The subtitles are grammatical and for dialogue distinguish speaker with green or yellow translations (plus some supertitle explanations from time to time). There are no extras.

—-

* When Yamamoto first appears at the Takeda castle, he says that he was drawn by the Takeda banner, which boasted that the Takeda clan was as swift as the wind (fu), as quiet as a forest (rin), as dangerous as fire (ka), and as immovable as a mountain (zan). The banners of the various armies are very prominent in the battle scenes.

©2016, Stephen O. Murray